‘Who will take care of my disabled child when I’m gone?’

It’s the question that keeps millions of parents awake at night. Here’s how you can start taking steps to plan for your child’s financial needs — now and for their lifetime.

WHEN EVAN BOHLE WAS ABOUT 6 MONTHS OLD, his parents, Tara and Dan, began to notice that he wasn’t hitting the developmental milestones his older sister Paige had at the same age. Six months later, shortly after the family moved from New Jersey to Denver for Dan’s job, the Bohles received a diagnosis that changed their lives: Their son had a rare neurological malformation of the brain called polymicrogyria. Evan, they were told, might not ever walk or talk and could require a lifetime of medical support and care. “We realized we were on a very different journey,” says Dan.

“We have to think about saving for two lifetimes — ours and his.”

Tara jumped into advocacy, searching for the best physical and occupational therapists in the area. Still, a larger question kept them up at night: What would happen to Evan when he was an adult and they might no longer be there to take care of him? “It’s the scariest thing in the world,” says Tara.

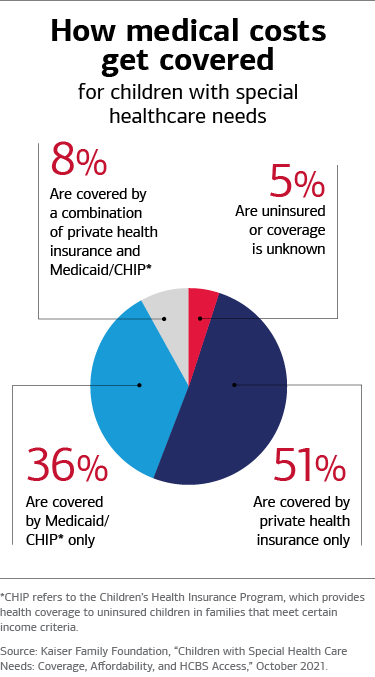

That’s a question faced by parents of the more than 14 million children in the U.S. who have special healthcare needs. One in four households has at least one child with a disability1 — a broad category encompassing everything from relatively mild disorders like attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder or dyslexia to conditions that severely limit individuals’ ability to care for themselves, such as severe autism, Down syndrome or a rare disease like Evan’s.

Moving beyond denial

“You don’t want to believe that you’re someone with that level of challenges,” says Tara, referring to the possibility that Evan will need care for the rest of his life. “At least initially, there’s a lot of denial,” she admits.

“The first thing parents need to do is educate themselves about their child’s needs, both now and in the long term,” says Merrill Wealth Management Advisor Donovan Filpi, who works with The Special Needs Team, a California-based advisor group focused on helping families with disabled children. Talk with other parents of similarly disabled kids, he suggests, to get an honest picture of what life can be like for the child and the family going forward.

Though, at 11, Evan is now able to walk and even talk through an electronic communication device, he still lives with intermittent paralysis, unpredictable seizures and intellectual, physical and behavioral delays. Many families with disabled kids try to convince themselves that things will somehow all work out. “And maybe they will,” says Dan, “but what we realized is that we have to plan for every outcome.”

Preparing for the future

To do that, parents may find it helpful to work with a financial advisor who has specialized experience helping families with medical issues and disabilities. The Bohles chose Merrill Private Wealth Advisors Michael Duckworth and Helen Sims Duerr of The Duckworth Haggerty Group. Their first piece of advice surprised the Bohles: Take care of your own financial future first. “Parents get so wrapped up in planning for their child’s future financial needs that they forget to plan for their own,” Duckworth notes. “But it’s critical to focus on your own retirement savings and long-term care plans,” Sims Duerr adds. “Once you’ve done that, you’re in a better position to start securing your child’s future.”

“A disabled child forces you to focus on the here and now, making it that much harder to think about what comes next,” says Filpi. He recommends searching out people with specific knowledge — from how to use your insurance to reimburse your child’s physical therapy to what changes might be needed to accommodate your home to your child’s disability.

As you plan for the financial future of your disabled child, these tips and insights can help.

“For those in need of ongoing care, there’s a common — and important — transition point in the late teens.”

Look into eligibility for government benefits. “Every child with a disability is unique,” says Cynthia Hutchins, director of Financial Gerontology at Bank of America, “but for those in need of ongoing care, there’s a common — and important — transition point in the late teens.” Once your child is 18 and a legal adult, you’re no longer automatically their legal guardian. That raises a host of considerations, including eligibility for ongoing government benefits. “The sooner you start to plan for that, the better,” says Hutchins. It’s ideal, though, to start putting the pieces in place before age 16, she adds. For more insights from Hutchins, read “Caring for children with special needs: A guide for new parents and caregivers.”

Learn about the available financial tools. “We have to think about saving for two lifetimes — ours and his,” says Dan. With The Duckworth Haggerty Group’s help, the Bohles familiarized themselves with the financial tools designed for the parents of disabled children. Ask your advisor whether either of these might be appropriate for you:

- Special needs trusts (SNTs). “Socking money away in a traditional trust may actually create a disadvantage for young adults with disabilities by disqualifying them for critical government benefits, including Social Security income and Medicaid,” notes Duckworth. What to do instead? Talk to your financial advisor about incorporating an SNT into your plan. The funds in such a trust will not be counted as your child’s assets when determining their eligibility for government benefits.

Let well-meaning grandparents know, too, not to leave inheritances — including real estate — to your child directly. Ask them to direct their gifts to the SNT instead. There are different types of SNTs that ultimately govern how the funds can be used for the benefit of your loved one — and whether those benefits need to be repaid to Medicaid at death. Be sure to also talk with your advisor about choosing an alternate trustee in the event that you or your spouse or partner can no longer act in that role.

“Socking money away in a traditional trust may actually create a disadvantage for young adults with disabilities by disqualifying them for critical government benefits.”

- ABLE accounts. ABLE (Achieving a Better Life Experience) accounts are similar to 529 college savings plans but for individuals who became disabled before the age of 26. They allow you to put away as much as $100,000 for disability-related expenses without compromising eligibility for government aid. Annual contribution limitations apply. As with a 529 plan account, investment appreciation within the account is tax-free, and while contributions are made after tax for federal tax purposes, some states may consider ABLE contributions to be deductible for state tax purposes.

Build a team. In addition to trusted friends, family and caregivers, Filpi recommends three core professional members to help you look after your finances: a financial advisor who knows the ins and outs of planning for people with disabilities, a certified public accountant who understands how to file taxes on a special needs trust, and an estate attorney who specializes in special needs trusts — one place to start your search is the nonprofit Special Needs Alliance, a network of attorneys who specialize in the field.

Create a letter of intent or a letter of wishes. All families need a will, a healthcare directive, a healthcare proxy and a power of attorney. It’s also critically important to specify who might serve as guardian and/or trustee for your disabled child when you are no longer here. Equally important, though, is a letter of intent or a letter of wishes — a document that informs any future trustees, guardians and caregivers of your child’s abilities, medical history, medications, likes and dislikes, sleep habits and more — everything from medication side effects to favorite ice cream flavors. “It’s an ever-changing handbook of care,” says Sims Duerr. “It’s the thing that allows parents to say, ‘I can’t control everything, but I can control this.’”

Consider where you live. “Helen told us we could never move out of Colorado,” jokes Dan. Sims Duerr was kidding, but only to a degree. “Programs and services for different types of disabilities can vary significantly by state,” she says, “and Colorado’s policies and programs are well suited to Evan’s particular needs.” Depending on your child’s disability, access to these programs could make a huge difference in their quality of life — and how much you’ll need to pay out of pocket for critical services.

Don’t shy away from hard conversations. If you have another child who is typically abled, as the Bohles do (their daughter, Paige, is now 14), you’ll want to talk to them at the appropriate age about what you’re planning financially for both of them. Do they want to be their sibling’s advocate when you no longer can? Or will you hire a professional trustee or guardian?

Daily life can still sometimes be challenging for Evan and his parents and sister — any family with a disabled child knows that every day can bring a new wrinkle. Diagnoses shift, new treatments become available, laws change, a parent might lose their job or get sick themselves. “The picture is always evolving; the work never ends,” says Duckworth.

But Dan and Tara no longer have sleepless nights worrying about Evan's future. “We feel comfortable that we’ve done everything within our power for Evan to live the best life he possibly can,” says Dan. “And that makes it much easier to enjoy and live in the moment with both our kids.”

A private wealth advisor can help you get started.

1 Health Resources and Services Administration, “Children and Youth with Special Health Care Needs,” NSCH Data Brief, June 2022.

Case studies are intended to illustrate products and services available through Merrill and/or Bank of America. The case study presented is based on actual experiences. You should not consider these as an endorsement of Merrill and/or Bank of America or as a testimonial about a client's experiences with us. Case studies do not necessarily represent the experiences of other clients, nor do they indicate future performance.

This article should be regarded as general information on healthcare considerations and is not intended to provide specific healthcare advice. If you have questions regarding your particular healthcare situation, please contact your healthcare, legal or tax advisor.

Merrill, its affiliates, and financial advisors do not provide legal, tax, or accounting advice. You should consult your legal and/or tax advisors before making any financial decisions.

Always consult with your independent attorney, tax advisor, investment manager, and insurance agent for final recommendations and before changing or implementing any financial, tax, or estate planning strategy.