What is tax-loss harvesting and how does it work?

Selling investments at a loss can help to offset gains and cut your tax bill. Here’s how it works.

WHEN YOU OWN INVESTMENTS, on any given day some of them are likely worth more than what you paid, while others may be worth less. Even in a rising market, individual stocks, bonds, mutual funds or exchange-traded funds (ETFs) may lag. And during a period of market volatility, investments that had been growing may drop below your initial purchase price.

These investment losses can be painful, but there may be an upside. They can potentially create an opportunity to reduce your federal income tax liability. Employing a strategy called tax-loss harvesting can offer a way to offset taxable capital gains — or even your ordinary income — with your capital losses.

Here’s what you need to know about this valuable tax-planning strategy, and what you can ask your advisors and your tax professional as you review your investment portfolio throughout the year.

How does tax-loss harvesting work?

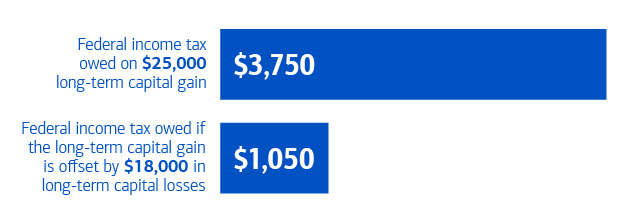

Outside of tax-advantaged retirement accounts, when you sell a stock, bond, mutual fund or ETF for more than you paid for it, you typically owe federal income taxes on your profit, which is called a “capital gain.” If you’ve owned the asset for more than a year, you’ll owe federal income tax at a long-term capital gains rate of up to 20%, depending on your taxable income. If you’ve owned the investment for a year or less, that profit is considered a short-term capital gain and is taxed as ordinary income.

Let’s say you also sell an investment for less than its original purchase price. With tax-loss harvesting, you may be able to deduct that capital loss from your capital gains, potentially resulting in a lower federal income tax bill. If you have more capital losses than capital gains — or no capital gains at all — you may offset up to $3,000 ($1,500 if married and filing separately) of your ordinary income with capital losses. And you may be able to carry forward any remaining capital losses to offset income in future years.

What’s the wash-sale rule?

Generally, this is a rule that discourages investors from selling an investment to capture a capital loss and then buying it back right away. You will trigger the wash-sale rule if you purchase the same investment, or what the IRS calls a “substantially identical” investment, at any point within the 61-day window beginning 30 days before the sale and ending 30 days after the sale. If you repurchase the same or a substantially identical security within that window, you won’t be able to claim the capital loss on your federal income tax return.

Suppose you buy a stock for $50 and sell it for $30, therefore realizing a capital loss of $20. But what if the price keeps falling to $25 a share, and you decide to buy it back a week later? You will no longer be able to claim the $20 capital loss. However, you may be able to add that $20 capital loss to the cost basis, or purchase price, of the repurchased stock. In this case, your new cost basis in the stock would be $45 instead of $25, which could reduce your future federal income tax liability if you later sell those shares and realize a capital gain.

![]() Did you know? When you inherit investments, your tax basis is generally the fair market value at the date of the previous owner’s death. Any historical capital loss on that investment does not carry over to you.

Did you know? When you inherit investments, your tax basis is generally the fair market value at the date of the previous owner’s death. Any historical capital loss on that investment does not carry over to you.

How can I avoid triggering the wash-sale rule?

The safest way to steer clear of the rule is to wait at least 31 days before buying back the investment you sold. But the “substantially identical” part of the rule creates some options. Once you’ve sold a technology stock, for example, you could buy a similar tech company stock without triggering the wash-sale rule.

You may have even more leeway with mutual funds and ETFs. You may be able to replace a fund you’ve sold with another one that has the same investment focus, such as another large-cap stock or one in a particular market sector.

Tap + for insights

When is the best time to take a loss?

While you can sell an investment for a loss anytime during the year, it might work to your benefit to wait until late in the year to take losses, so that you’ll have a better idea of the capital gains across your portfolio and your federal income tax liability for the year.

Especially during periods of heightened market volatility, reviewing your portfolio regularly for losses may allow you to take advantage of short-term swings. If you work with a Merrill advisor, ask about Merrill’s Tax Efficient Management Overlay Services, which can analyze your portfolio for potential tax-loss harvesting and/or other tax management approaches for eligible investments throughout the year.

![]() TIP If you’re selling part of your stake in a holding that you purchased bit by bit over time, you may be able to lock in the biggest tax loss by identifying and selling those shares with the highest cost basis, or purchase price.

TIP If you’re selling part of your stake in a holding that you purchased bit by bit over time, you may be able to lock in the biggest tax loss by identifying and selling those shares with the highest cost basis, or purchase price.

What are some other reasons to sell a losing investment?

A loss alone is not necessarily a reason to sell — you may still believe it is a good investment for the long term. There are many reasons to sell a stock, bond, fund or ETF, from a change in the economy or the outlook for a sector, to your need to rebalance your portfolio or access cash. If the sale results in a capital loss — and you can use that capital loss to reduce your federal income tax liability — that could be something of a silver lining. But your overall plan for your investments should be your starting point.