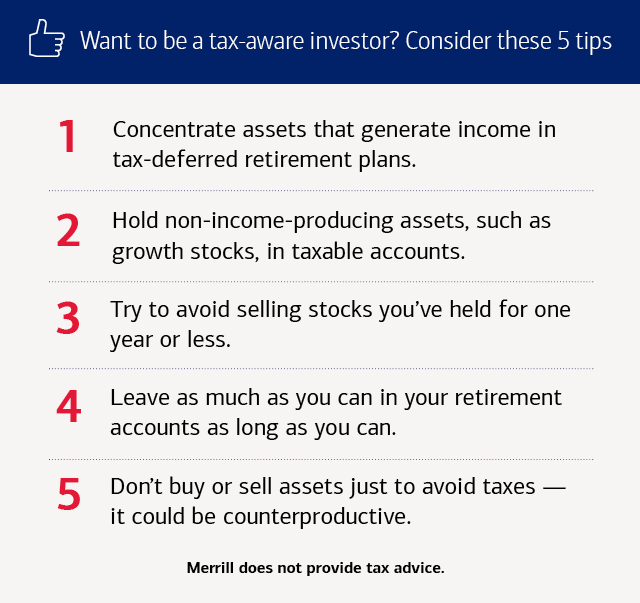

How should taxes factor into your investment decisions?

Answering these five questions can help you make informed decisions — and potentially lower your tax bill

TAXES AREN’T JUST A ONCE-AND-DONE THING. There are plenty of steps, beyond the last-minute rush to file every April, that investors can take to help reduce their tax liability, says Vinay Navani of the accounting firm WilkinGuttenplan P.C.* In fact, he adds, “It’s crucial to make tax considerations an integral part of every investment decision all year round.”

And you don’t have to go it alone. Your financial advisor can assist with strategies designed to help potentially lower your tax bill and increase your returns. To see what you can do to help minimize your federal tax bill, start by asking these five questions (note state and local taxes may vary):

What types of assets should I consider owning?

Before you decide on the mix of stocks, bonds and cash instruments that makes the most sense for you, it’s helpful to understand how the IRS treats the income from each. Ordinary income, including interest payments on bonds and cash, is currently taxed at individual rates as high as 37%. Profits from the sale of stocks you’ve held for more than a year qualify as long-term capital gains, and the capital gains tax rate currently maxes out at 20%. For both types of income, a 3.8% net investment income tax may apply as well. (And future tax law changes are always a possibility.) Also, be aware that if you hold a stock a year or less and sell it at a profit, the gain will be taxed as a short-term capital gain — which is taxed at the same rate as ordinary income.

Should I invest in a tax-deferred or taxable account?

The investment income you earn on assets held within a 401(k) or IRA generally isn’t taxable before withdrawal. For that reason, you may want to place holdings that generate ordinary income — bonds or non-qualified dividend-producing stocks — in tax-deferred retirement accounts. (In retirement, your withdrawals may be taxed at your ordinary income rate — or potentially not taxed in the case of a Roth account, provided certain conditions are met.)

By contrast, it’s often smart to hold non-income-producing assets, such as growth stocks, in taxable accounts. Even if their values increase substantially, you generally won’t experience any tax consequences until you sell them. “Your advisor can help you think through the tax implications of where you hold different types of investments,” Navani says.

Special consideration may be given to municipal bonds, which are generally exempt from federal (and, in some cases, state and local) taxes, notes Navani. But that tax treatment applies when you hold the bonds directly or in a mutual fund, he adds. When muni bond income is distributed from a retirement account, it’s generally treated as ordinary income and is taxable — unless it is a qualified distribution from a Roth account. Ask your advisor whether muni bonds, which often have lower yields than other bonds, may be an appropriate choice for your taxable portfolio.

“It’s crucial to make tax considerations an integral part of every investment decision all year round.”

— Vinay Navani,

CPA and shareholder, WilkinGuttenplan P.C.

When should I begin taking withdrawals in retirement?

It’s often wise to leave as much as you can in your tax-deferred retirement accounts (e.g., traditional 401(k) account or traditional IRA) for as long as possible so those investments can continue to grow on a tax-deferred basis. You generally don’t need to take required minimum distributions (RMDs) from your tax-deferred retirement plan, such as a traditional 401(k), or a traditional IRA until April 1 of the year after you reach 73.1 If you’re still working, you generally don’t have to take RMDs from your current employer’s plan.

If you need money beyond your RMDs to meet living expenses — and don’t want to deplete your retirement accounts — your advisor can help you review other income sources, such as cash or assets in taxable accounts. You can then make any necessary adjustments to your portfolio, keeping the tax implications in mind.

How can I make tax-efficient charitable donations?

Even if you aren’t able to deduct charitable donations from your taxes because you take the standard deduction, you still have ways to give in a tax-efficient way. By donating appreciated shares of stock directly to charity, you may be able to avoid the federal capital gains taxes that would apply if you sold the stock and then donated the proceeds. The deduction for long-term capital gain assets is equal to the stock’s fair market value. With a short-term gain, your deduction is the fair market value or what you paid for the asset, whichever is lower. Your tax advisor can help you consider whether donating appreciated stock makes sense for you.

If you’re retired and age 70½ or older, you can make a donation directly from your traditional IRA to a qualified charity in the form of a qualified charitable distribution (QCD), therefore satisfying all or a portion of your RMDs (after age 731) and potentially reducing your taxable income. The cap is adjusted annually for inflation (for this year’s maximum amount, see our annual limits guide). QCDs are subject to additional rules and limitations. Your tax advisor can help you understand the requirements and determine whether making a QCD could help you lower your taxable income.

How might taxes figure into any decision to buy or sell assets?

“Your advisor can help you think through the tax implications of where you hold different types of investments.”

— Vinay Navani,

CPA and shareholder, WilkinGuttenplan P.C.

In a good year, you may want to lock in gains by strategically selling appreciated assets. “But try to avoid selling stocks you’ve held a year or less since they’ll be taxed at your individual rate for ordinary income, while you’ll pay no more than a 20% tax on long-term investments,”2 Navani says.

When you sell, you may be able to take advantage of tax-loss harvesting, or selling investments that have dropped in value to offset taxable gains. If you have more capital losses than gains, you may generally deduct up to $3,000 of capital losses per year from your ordinary income (or $1,500 if married and filing separately). And if your net capital losses exceed that yearly limit, you may generally carry over the unused losses to the following year. Your advisor can look for opportunities to do this throughout the year.

Bear in mind that if you wait until late in the year, you’ll be dependent on what happens in the markets in the year’s final weeks. And if you buy substantially identical stocks within 30 days before or after the sale, it will be considered a wash sale, and any losses will be disallowed.

While taxes should be factored into your investment decisions, buying or selling assets solely to avoid taxes could be counterproductive. For example, in a strong market, you might look at capital gains taxes as a necessary cost of capturing substantial gains, Navani says. By contrast, investors who hold on to assets for fear of owing taxes could lose out if those assets drop in value.

All the more reason to work with your advisor to think through every consideration about your life and financial goals — not just the federal income tax implications — as you make your investment decisions throughout the year.

A Private Wealth Advisor can help you get started.

* As a CPA and shareholder at WilkinGuttenplan P.C., Vinay Navani is not affiliated with Merrill. Opinions and views expressed are his, do not necessarily reflect the opinions and views of Merrill or any of its affiliates, and are subject to change without notice. Merrill, its affiliates and financial advisors do not provide legal, tax or accounting advice. You should consult your legal and/or tax advisors before making any financial decisions.

1 The required beginning date for RMDs is generally April 1 of the year after you turn age 73. You are required to take an RMD by December 31 each year after that. If you delay your first RMD until April 1 in the year after you turn 73, you will be required to take two RMDs in that year. You may be subject to additional taxes if RMDs are missed. Please see your tax advisor regarding your specific situation.

2 A 3.8% net investment income tax may also apply.

Merrill, its affiliates, and financial advisors do not provide legal, tax, or accounting advice. You should consult your legal and/or tax advisors before making any financial decisions.